Revenue — While it may still be early days for the tariffs, we have some evidence of their impact in terms of revenue generated for the government. The Daily Treasury Statement shows that since tariffs were announced in April, cumulative customs and excise tax revenue has run about $88 billion higher vs the same period in 2024.3 Additional revenue can be used to offset government spending elsewhere, a potential boon to federal finances. However, with the federal deficit running at nearly $2 trillion in 20254, we feel the impact is likely to be modest, absent further changes.

Payment — Who ultimately pays for tariffs? This remains the most important question for many investors. At the end of June, Goldman Sachs and BNP Paribas separately estimated that U.S. firms had absorbed around 60% of the total cost of tariffs, with foreign firms and U.S. consumers absorbing a further 20% each. But as the situation evolves, we believe those early estimates are likely to change (more below).

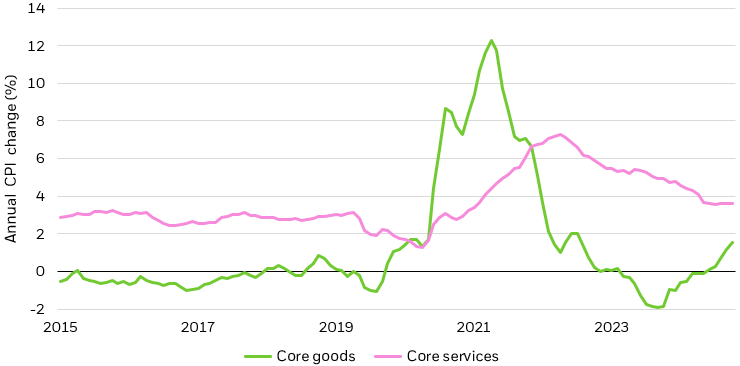

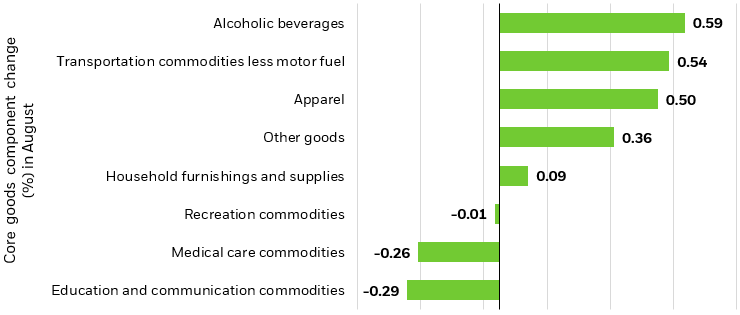

Inflation — While perhaps not as large or as fast as some market participants anticipated, we see some evidence of higher tariffs in inflation reports. Parts of the CPI basket that are highly exposed to supply chains in some of the highest-tariffed regions, such as apparel, furniture, and sporting goods, have seen prices rise in recent months. And there may be evidence of indirect effects as well. As we learned during the pandemic, consumers who are unable to spend on services may pivot to goods; we feel the same effect is likely happening to some extent in reverse, as consumers put off by higher tariffs have pivoted to services, with evidence of such substitution found in higher concert, dining, and lodging prices.5 Still, we have not seen future inflation expectations become unanchored, and the acceleration in inflation from the summer was not enough to prevent the Federal Reserve from resuming rate cuts in September and October.